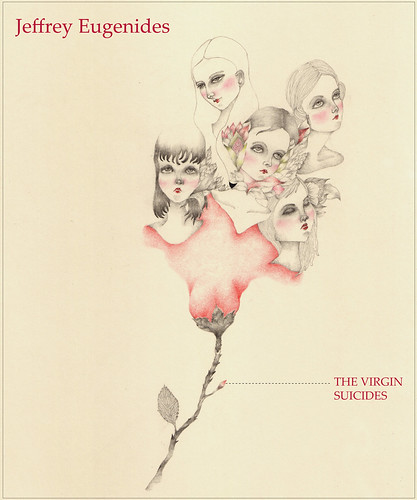

Eugenides, Jeffrey. The Virgin Suicides. Warner Books, published by arrangement with Farrar, Straus and Giroux.: New York. 1993.

Jeffrey Eugenides is an American novelist and short story writer. Eugenides published his first novel, The Virgin Suicides, in 1993. It was later adapted into a movie that was directed by Sofia Coppola and released in 1999. Eugenides second book, Middlesex, was published in 2002 and won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. His third book, My Mistress’s Sparrow is Dead will be published in 2008. Eugenides has also published several short stories, including “Air Mail,” which was in the 1997 edition of Best American Short Stories. In The Virgin Suicides, Eugenides’ writing balances between the external situations and the internal conflicts, providing great insights using both. Sometimes dark and frank, sometimes poetic and meandering, Eugenides captures the confusion and obsession surrounding his multiple narrators.

Eugenides also shows the narrators’ delusional romanticism by using elements from classic plays and literature. One of those is the decision to use the first person plural narrative in the form of a Greek chorus. Those stories surrounded tragedies, and Eugenides crafts his book in the same way as all of the female children in a home kill themselves. The observant narrators are also struck down by the tragedy because their lives are wrecked by their obsession.

“As soon as we learned the names of these brochures we sent for them ourselves to see where the girls wanted to go. Far East Adventures. Footloose Tours. Tunnel to China Tours. Orient Express. We got them all. And, flipping pages, hiked through dusty passes with the girls, stopping every now and then to help them take off their backpacks, placing our hands on their warm, moist shoulders and gazing off at papaya sunsets. We drank tea with them in a water pavilion, above blazing goldfish. We did whatever we wanted to, and Cecilia hadn’t killed herself: she was a bride in Calcutta, with a red veil and the soles of her feet dyed with henna. The only way we could feel close to the girls was through these impossible excursions, which have scarred us forever, making us happier with dreams than wives.” (Eugenides 169)

This passage personifies the Greek chorus. The men are characterized as being observational to the degree that they buy brochures to observe where the girls wanted to go. Even in the end, they observe the girls’ suicides, but do not actively do anything about it. Only in their many fantasies do they do anything more than observe. In the one instance when they attempt to participate in the girls’ lives (taking them on a collective date), they are not chosen and simply observe the date taking place. As adults, they are happier with the fantasies from those observations than any real life interactions. This goes back to their dreamy romanticism. In their minds, they are living out the fate of tragic lovers, but Eugenides casts them in the chorus to reveal to the reader that they are merely observers and play no active role in the girls’ lives or deaths.

However, Eugenides includes a tragic lover in the book, but he updates Trip Fontaine to show the reality of the classic figure.

“Years later he was still amazed by Lux’s singleness of purpose, her total lack of inhibitions, her mythic mutability that allowed her to possess three or four arms at once. “Most people never taste that kind of love,” he said, taking courage amid the disaster of his life. “At least I tasted it once, man.” In comparison, the loves of his early manhood and maturity were docile creatures with smooth flanks and dependable outcries. Even during the act of love he could envision them bringing him hot milk, doing his taxes, or presiding tearfully at his deathbed. They were warm, loving, hot-water-bottle women. Even the screamers of his adult years always hit false notes, and no erotic intensity ever matched the silence in which Lux flayed him alive.” (Eugenides 87)

Supposedly, Trip’s romantic trysts after Lux are forever tainted by one encounter with her. His life is a wreck, and the narrators find him at a rehabilitation center drying out from years of drug abuse. This paints a particular picture of a tragic lover. However, Trip was heavily using drugs before he met Lux, so the reader knows she did not cause that downfall. And after their brief romantic encounter, Trip has intercourse with Lux and leaves her alone afterward, saying, “It’s weird. I mean, I liked her. I really liked her. I just got sick of her right then.” (Eugenides 138-139) Other small details show the reality of Trip’s tragic love, like during the first time he sees Lux, Trip recalls seeing shimmering lights, but the narrators believe it was most likely a result of being high.

In the passage on Trip’s encounter with Lux, Eugenides hints at another classic figure from Greek tragedies: the Siren (“Even the screamers of his adult years always hit false notes…”). Eugenides refers to them again through the chorus of narrators.

“It didn’t matter in the end how old they had been, or that they were girls, but only that we had loved them, and that they hadn’t heard us calling, still do not hear us, up here in the tree house, with our thinning hair and soft bellies, calling them out of those rooms where they went to be alone for all time, alone in suicide, which is deeper than death, and where we will never find the pieces to put them back together.” (Eugenides 248-249)

While the narrators compare themselves to the Sirens (only in reversal in the belief that their calls could have saved the girls), it is actually the girls that are the Sirens. Even though they are mostly silent, the boys are drawn into their beauty (mostly referring to them as a singular entity, “the Lisbon girls”) and they doggedly follow the girls, which wreck their lives, as a result. Several key words in the above passage harkens the Sirens (“calling,” “alone for all time,” “deeper”). Eugenides also cleverly twists the siren song by placing the men “up here in the tree house,” instead of under the waves in the sea.

By updating these classic forms, Eugenides emphasizes the reality behind romanticism. In this way, he negates a theory that the girls’ suicides were a result of a degenerating society; thus opposing that same common theory that arises during every tragedy throughout history.